Personality testing is based on the possibility of a business utopia where employees can be categorized and slotted into the right spot or the right team. However, this assumes that humans are consistent and static, which we really are not.

I first encountered a personality test at one of my earliest office jobs barely out of my teenage years. I was working as a temp and the president asked me to help him decipher personality tests he’d given to potential job candidates. Unfortunately, the tests were delivered to him as coloured charts and he was colourblind, so he needed me to tell him what they said.

I first encountered a personality test at one of my earliest office jobs barely out of my teenage years. I was working as a temp and the president asked me to help him decipher personality tests he’d given to potential job candidates. Unfortunately, the tests were delivered to him as coloured charts and he was colourblind, so he needed me to tell him what they said.

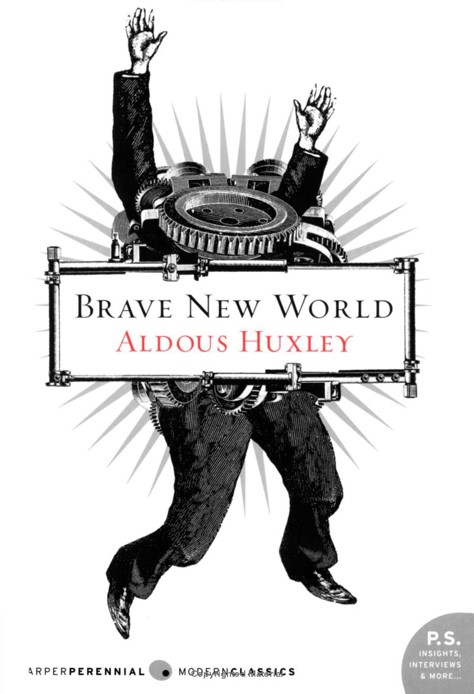

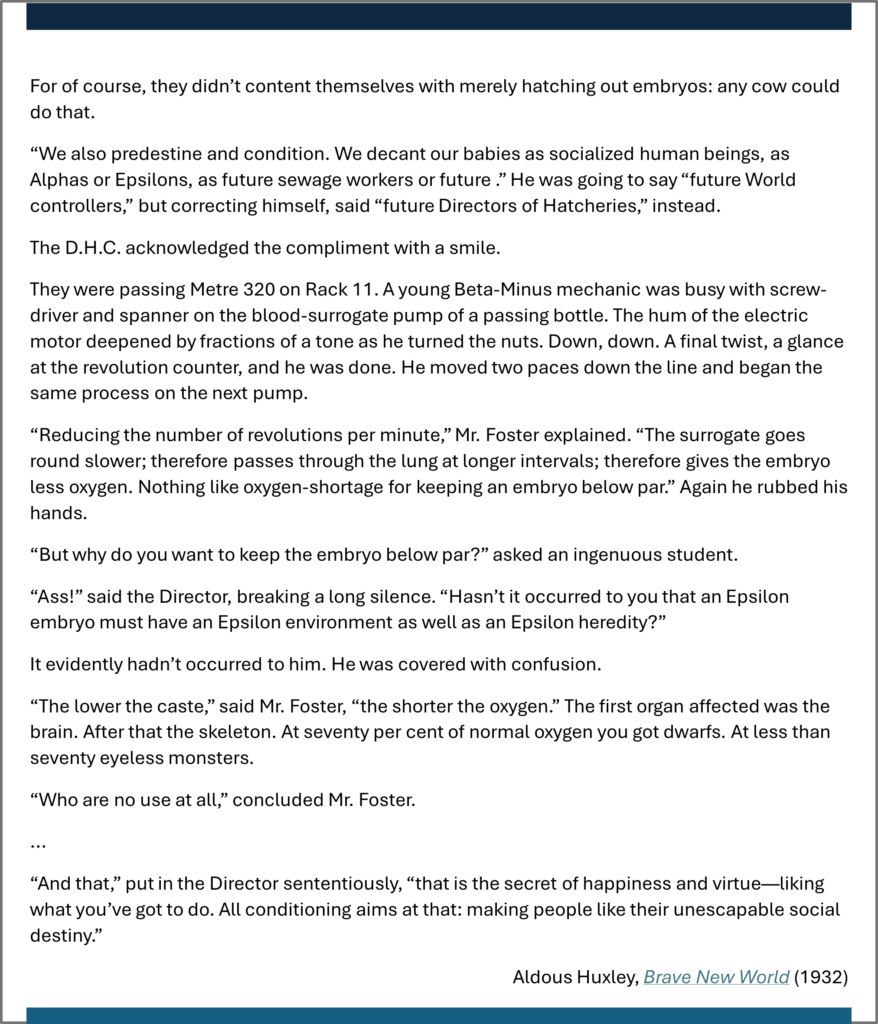

What I thought back then was “Is it possible that a test can really determine who you are and what kind of worker you will be?” and “If it can do it why doesn’t everyone do this?” But I also thought that this looked a bit like a scene from Aldous Huxley’s novel Brave New World where humans are incubated in a lab and bred to be workers of a certain type.

In the novel, embryos that will be given jobs that require less intellectual rigour are denied oxygen at key developmental stages to stifle brain development. Here’s a passage from the book where a group is being given a tour of the baby factory.

One of the things that makes Huxley’s book so compelling is the fact that creating people to like their jobs is both benevolent and insidious. Certainly, there is a kind of desire for the utopian world where every person gets up in the morning and looks forward to their job, whether that is cleaning sewers, designing new sewers, or making decisions about city budgets for sewers.

One of the things that makes Huxley’s book so compelling is the fact that creating people to like their jobs is both benevolent and insidious. Certainly, there is a kind of desire for the utopian world where every person gets up in the morning and looks forward to their job, whether that is cleaning sewers, designing new sewers, or making decisions about city budgets for sewers.

A Bit of a Tangent

Utopia is a word made up by Sir Thomas More in 1516 for his book Utopia, which was about an island in the New World. It is a book which may have influenced Huxley’s title of Brave New World. More’s original book made up the word utopia because it comes from the Greek ou meaning “no or not” and topos meaning “place.” Literally, a utopia is a “no place” or “nowhere” or an impossibility. Oddly, the Greek ou for “not” is pronounced in English the same as eu for “good.” More noted this discrepancy, and felt that eu might have been a better choice: “Wherfore not Utopie, but rather rightely my name is Eutopie, a place of felicitie.”

In case you’re interested, More’s vision of a perfect society included slavery and it was still a patriarchy, but a variety of religions were allowed and widows could become priests. There was free health care and euthanasia allowed by the state, and priests could marry and divorce, all of which was quite radical at the time (and is still quite radical, for some, today). More made the law in his utopia so simple and intuitive that there was no need for lawyers, but the punishment for transgressions seemed to most often be slavery, which was clever because it addressed the biggest problem of any utopia, which is who is going to do the dirty work that no one wants to do.

In case you’re interested, More’s vision of a perfect society included slavery and it was still a patriarchy, but a variety of religions were allowed and widows could become priests. There was free health care and euthanasia allowed by the state, and priests could marry and divorce, all of which was quite radical at the time (and is still quite radical, for some, today). More made the law in his utopia so simple and intuitive that there was no need for lawyers, but the punishment for transgressions seemed to most often be slavery, which was clever because it addressed the biggest problem of any utopia, which is who is going to do the dirty work that no one wants to do.

Critics still argue about the text, not knowing why More wrote it and whether he was serious in his ideas or if he was being satirical, not only because of his ideas about freedom of religion, some freedom for women and free health care, but because there was so clearly things you couldn’t do in this utopia (e.g., sex outside marriage) or think in this utopia (e.g., atheism).

The reason we don’t know how to read the work is because a utopia is, as its name suggests, impossible. Each and every utopia quickly becomes a mix of “e-u” topia or “good place” if you follow all the rules or a dystopia or “bad place” if you don’t. And that sounds less like a utopia and more like regular old society.

End of Tangent

In essence, the problem of a utopia is that it assumes that humans are stable and all agree on all aspects of society. But society is made up of maddeningly inconsistent humans. And coming back to our topic of personality testing it is this inconsistency that makes the claims of personality tests suspicious. This kind of testing suggests that it can offer a utopia where workers can be categorized in order to put them into jobs where they can be efficient and happy in order to make the company the most money.

The problem with these tests and programs is that they don’t take into account the human. Simply, there will always be jobs no one wants to do and there will always be people who don’t fit into a neat category or who shift and change out of a category over time, even a short period of time. People have wishes and dreams and are constantly learning and growing and this all must be stifled if you want a utopia where humans are easily manageable. And this is true whether that utopia is a city or a factory.

What the literature of utopias show us is that humans are not machines; and utopias—to work for everyone—must have a group of people that have consistent and stable human behaviours so they can be used as data points and slotted into place. But even in Huxley’s Brave New World where embryos are manipulated both chemically and through socialization to be content and even happy with the jobs they are given, it doesn’t work. Humans are tricky, slippery, shifting and changing over a lifetime in our likes, our dislikes, our desires and our understandings of what is important to us and to the world.

Comparing Fictional Utopias to Business

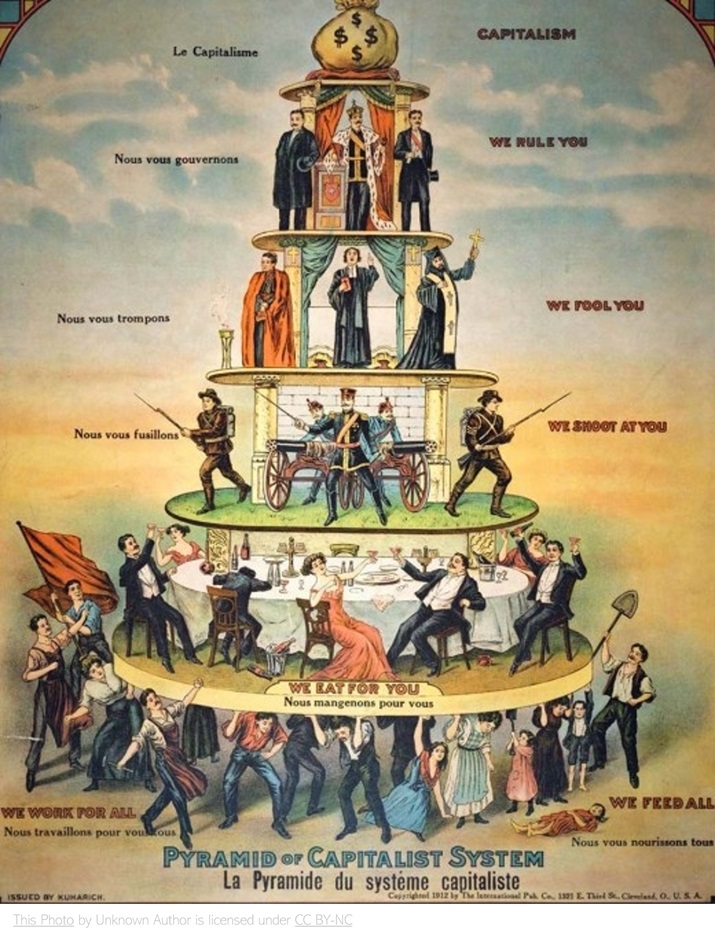

Back in the real world! A desire for a completely consistent and hyper-regulated SOCIETY manifests itself through fascist regimes, authoritarian dictatorships, and theocracies where consistency is prioritized over happiness and freedom of movement and thought.

And while no person in BUSINESS would admit to any correlation to this kind of social manipulation and extremism, this search for a utopia where people can be slotted into place does exist in business. We see it everyday through the use of personality tests and computer algorithms in the hiring process. The notable difference between a social utopia and a business utopia is that it is potentially, tantalizingly, more possible in business because unlike society, if there are outliers or if someone doesn’t fit in your business model, you don’t have to put them in jail or make them slaves, you just don’t hire them or you fire them and they disappear from your community and are no longer your concern.

Firing People to Achieve Business Utopia

But firing people after you’ve gone through the trouble and expense of the hiring, training and on-boarding processes is tiresome and expensive. Especially if that person negotiated a very sweet severance package, like Yahoo CEO, Scott Thompson, did. Thompson was fired in 2012 after only 5 months on the job because he lied about his degree on his resume. His severance package was originally negotiated at $16 million but he had to make do with $7 million because he was being terminated with cause.

Lying on Your Resume is a Human Inconsistency

This lying to get a job is one of the markers of being human. It is an unknowable and unpredictable factor. And it is pervasive not only at entry-level positions, where it has become almost necessary with the unreasonable expectations of certain positions, but at high levels.

An article by the New York Times at the time of Thompson’s firing noted faked credentials from “a former Notre Dame football coach, chief executives of RadioShack and Bausch & Lomb, a director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency and an MIT admissions director.”

This is the crux of why utopias are truly “no places”–they simply cannot exist.

But the desire, especially in business, to have humans be data points is so compelling that there has always been a market for those claiming to have cracked the code of the human worker.

Myers-Briggs: The Fake We Still Want to Believe

The desire to know ourselves is hardwired into us: it is the reason we read fiction, it is the reason there are astrologists, and it is the reason that business continues to convince itself that through testing it can see a human as a data point and then slot them into the right job where they will be happy and productive.

There are hundreds of these kinds of systems that exist. Some we dismiss even as we are filling out that questionnaire. We don’t really think that some random internet test will truly identify us as a Slytherin or a Hufflepuff. But other systems are taken seriously and make millions of dollars claiming to be able to do something very similar.

The poster child for these tests is the Myers-Briggs test, which continues to be successful even though it is not based on anything scientific and has been debunked over and over again.

Just as an aside, the fraught history of the test is acted out on Wikipedia where the English version of the site calls the test “pseudoscientific” but the Simple English version of the site says it is “based on psychology” and, notably, was made because the two women “thought that the set of questions would help women be happier and work better.” So which is it? Pseudoscience or psychology?

A Bit of History on the Test

The Myers-Briggs system was invented by the American Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers in 1944. Neither of them had training in psychology but were influenced by the 1921 book Psychological Types by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung. Briggs first wrote about her ideas in a 1926 article for The New Republic with a title that could have come from any women’s magazine today. It was titled “Meet Yourself Using the Personality Paint Box.”

Notably Jung’s theory, which was just a theory and never tested, proposed 32 types, but because 16 of them were difficult to measure on a questionnaire, Myers-Briggs simply abandoned them. The remaining categories were set up as neat binaries. According to its own website, there are four of these binary categories:

· you “direct and receive energy through Extraversion (E) or Introversion (I)

· take in information with Sensing (S) or Intuition (N)

· come to conclusions using Thinking (T) or Feeling (F)

· and approach the outside world through Judging (J) or Perceiving (P).”

After taking the test, you are given four letters–one from each of the four binary categories–that define you as a type.

The trouble with humans and binaries is that most people cluster in the middle. Think of politics. The vast majority of people are a little bit to the left on some issues and a little bit to the right on others. There are people who sway further in one direction on many issues but truly radical all-in-on-one-side people are actually quite rare. This middle cluster doesn’t work for binaries. A friend of mine, for example, told me he was fiscally conservative and socially liberal, so in a binary system of, say, American Republicans and Democrats, where do you put someone who clearly straddles that middle line and exists in both camps?

Myers-Briggs didn’t worry about this. Their focus was to categorize people and you have to draw the line somewhere. So the test simply draws a line where everything below it is one thing and everything above it is another. It is a bit like stating that even though most people walk in the middle of a sidewalk, those who are slightly to the left or slightly to the right of the middle have identifiable and concrete differences.

The test really took off in 1962 when it was added to the Educational Testing Service in America. It is now estimated that 50 million people have taken it. Most recently, during the Covid pandemic, it came back as a fad among young South Koreans who were using it on a website called 16Personalities in order to find dating partners. That site claims to have administered well over a billion tests. According to the website, “Only 10 minutes to get a “freakishly accurate” description of who you are and why you do things the way you do.” This is a pretty strong assertion when one scientific study found that “More than one-third of people receive different four-letter types after a four-week period,” and when “Other studies have shown that over a five-week period, about 50 percent of people will receive different four-letter types.” It is clear that “consistency and accuracy of MBTI types is by far the exception, not the rule.”

Again, we return to that utopian necessity for consistency, which this test fails to find.

And yet it continues to exist and be used. Or as noted psychologist Adam Grant said back in 2013, it is the “fad that won’t die.”

Personality Tests: Where Business Fights Fiction

One thing that interests me about personality tests is how oblivious they are to the reality of the human that art has always known. Humans are messy and art is open to this exploration.

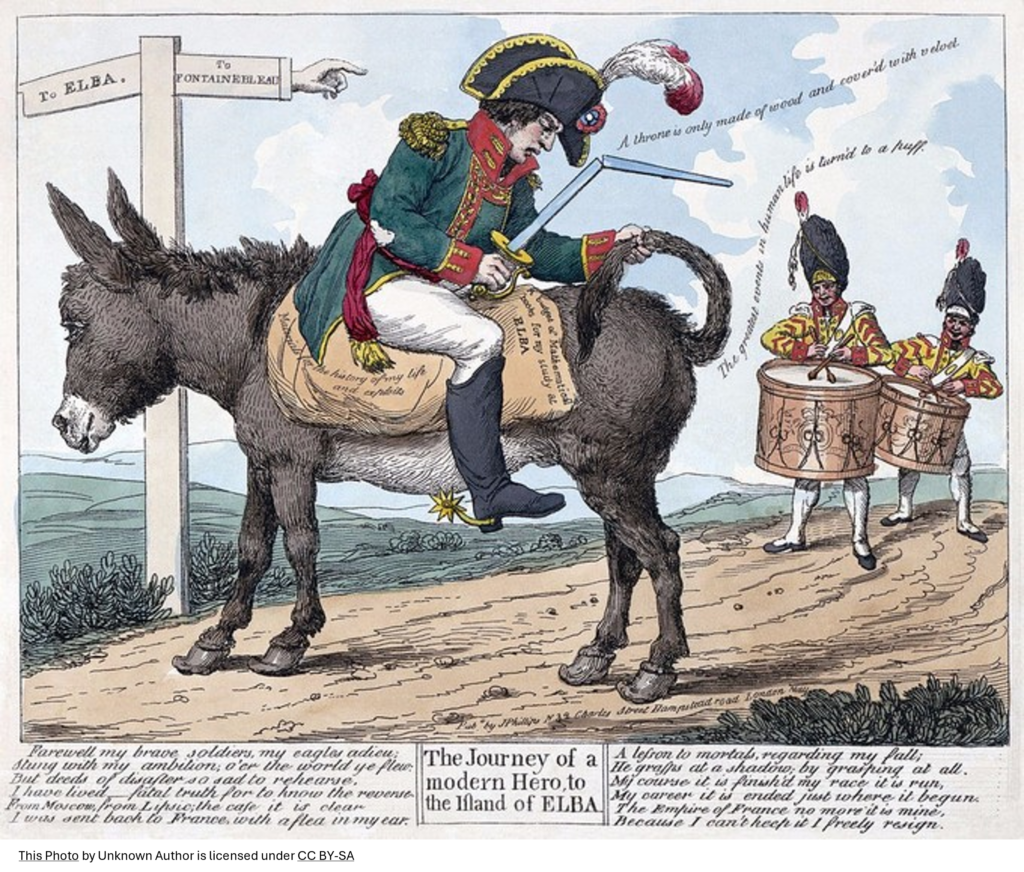

Let’s consider Leo Tolstoy. His huge and historical novel, War and Peace from 1867 was, at the time, a unique effort to join what people thought of as the hard written history of the Napoleonic campaign into Russia in 1812 with the soft exploration of the human elements of it. But he wanted to challenge the idea of hard facts in history.

He wrote of the difference:

“The historian is sometimes obliged, by bending the truth, to bring all the actions of a historical figure under the one idea he has put into that figure.”

So, for example, if a historian sees Napoleon as a genius strategizer of war, then the historian will pick and choose elements of history that support that idea or even bend the truth to further that perception.

Tolstoy then compares this to the artist. He writes, “The artist, on the contrary, sees the very singularity of that idea as incompatible with his task, and only trie[s] to understand and show not the famous figure but the human being.” (Tolstoy, p. 1219)

This is the problem with personality tests that promote themselves as “hard science” so they can claim to remove the human element and categorize people as a consistent data point.

The Myers-Briggs system, like many of these systems, needs to bend the truth to get people to fit into “hard science,” and there is just enough of the truth in the system to make people think it is an easy answer and a nice, neat box.

A Bit of a Tangent

Personality and career assessments, like astrology, rely on something called the Barnum or Forer Effect.

You may recognize the name Barnum after the famous Phineas Taylor Barnum who ran the Barnum and Bailey Circus; he was the main character of the Hugh Jackman movie, The Greatest Showman, and he loved to showcase a good hoax. Barnum is credited with the line, “There’s a sucker born every minute” although there is no evidence he actually said that. He wasn’t the type of person to disparage his customers because they made him a rich man, so he likely didn’t say this. However, he might have thought it because he saw first-hand how the line between fact and fiction is a very wiggly one for humans. For example, crowds continued to buy tickets to see his Cardiff Giant, which was supposedly a 10-foot petrified man, even after it was shown to be a hoax. In fact, YOU can still buy tickets to see it at Marvin’s Marvelous Mechanical Museum in Farmington Hills, Michigan.

The Barnum or Forer Effect is the effect of giving such vague information that it can pertain to almost anyone. People then translate that vagueness into something specific in their own lives and then feel like the information is shockingly accurate.

If you’d like to see this effect in action, here’s a clip from Derren Brown’s television show. Brown is a noted mentalist and in one episode he uses the Barnum or Forer Effect in three different continents in three different languages where he asks groups of people to give him a personal item and he will go away and use the energy from the item to help him write individual, very specific assessments of who they are. He takes the items and goes off to write these assessments. When he returns, the groups gather again and he gives each person their own envelope with their own individual assessment. They separate to the four corners of the room and read. The camera crew records all their shock and surprise about how accurate Brown is and how he correctly identified specific aspects of their personalities, histories, wants, and desires. The big reveal comes when Brown brings them back together for a final time and tells them, as a group, that not only do they all have the same assessment but Brown wrote this vague and generic assessment weeks before he met them.

The reason this worked so well is because of the Barnum or Forer affect where the assessment was vague and offered several different points. People glommed onto the items that they could relate to their own lives and by relating it to their own lives made it less vague and more specific in their own minds. And they simply ignored anything that didn’t fit. Thus it felt like Brown had somehow seen into their souls.

End of Tangent

You may ask yourself, “so what?” Even if personality tests are bogus, who really gets hurt by them?

One of the reasons I have a problem with these assessments is that at their best they simply encourage people to look at themselves and how they like to work, and then think about that so they can know themselves a bit better. But this encouragement only works if the person taking the assessment is guided to reflect in this manner. First, you don’t need a test to reflect on yourself and second, in most cases these assessments are not about reflection or personal growth. They are used in hiring practices or team building where they carry a lot more weight about a person’s life than they can or should.

At their base, these assessments divide people. They cannot help but put people into hierarchies, in just the same way that Huxley’s Brave New World divides people into Epsilons and Alphas. They set up a caste system. They claim to be helpful by opening up an understanding of individuals and allowing people to communicate as equals with different strengths, but what they actually do is pit people against, over, and above others.

Making a Caste System

I did one of these personality/career assessments in academia in what was supposed to be a fun, afternoon workshop for a bunch of professors and administrative and teaching staff. The system, I won’t name it, was in-depth, dozens of pages long that I had to complete before the workshop. An expert on the system was paid to come in and help us interpret the results. But in going around the conference table and being labelled by this stranger and the system, one professor became very angry at being typed as a “supporter” person. Well, no professor, who has worked so hard to get where they are wants to be told they are the person who should be making cookies for the team while others do the real work, sweetheart.

No one wants to be identified as a supporter in a meeting with their colleagues who just a moment before were your equals. In an instant, if you were to believe the pseudoscience, a person you’d worked with and seen starting initiatives and producing research was suddenly dropped to a supporter role. Denied the right to be seen as an innovator, leader, or creative force. The fact that we all had invested so much time and money into this assessment–after all, we took personal time to fill out the lengthy questionnaire and were now taking several hours out of a work day to think deeply about the results–only added to the legitimacy that we had been wrong about this professor all along. In a matter of seconds, someone’s reputation changed right in front of our eyes.

The expert in the system, who was running the meeting, tried to placate the professor—who was obviously angry—by insisting that supporter types had important roles—like wedding planners, she suggested—but she wasn’t fooling anyone. She didn’t say her test created a caste system, but it did. The personality categories had a clear hierarchy that everyone could see. That professor knew it and everyone in that room knew it, and we all knew that the professor had been forever tainted and reduced by the category the system had assigned.

From a communication perspective, it bothers me that these systems are there to smooth over the business environment, make people happy by correctly identifying where they would fit best, but they actually do the opposite. They create divisions and they create competition. Take that professor who was angry at being labelled a “supporter” type. What if the label had been from Myers-Briggs and was the INFJ personality type that is, arguably, the rarest type with just 1.5% of the US population having it? This type is known as the insightful visionary—in other words, the kind of people who change the world and still have people like them. This is definitely the top of the pile for Myers-Briggs and if that professor had been identified as that, I’m sure there would have been no problem because that type is clearly the winning one.

If you have any doubt about there being a winner in personality type systems, let me tell you that when I was researching which Myers-Briggs type is the rarest, I found there was heavy competition and anger as people fought for the top spot. If their type wasn’t the top spot, they argued that the data was flawed.

Conclusion

How do we create better teams and working groups or communities without personality testing?

Identifying people as data points claims to be a way toward better understanding, better communication, more efficiency, even happiness. In other words, better business. But this is a utopia—a no place—that disregards the fact that people are frustrating. They are not simple, not consistent, not scientifically calculatable, and usually pretty messy.

These systems encourage us to lie about what makes humans unique. They set up caste systems where people are able to dismiss real concerns as just being a manifestation of a type. “Oh, Janet is just an ESFP. She’s just complaining. She’s get over it!”

Ultimately, these system do the exact opposite of what they claim to do: they do not lay bare the clear nature of a person and they do not even make it easier for managers to build teams. And at their worst, these tests push human-to-human communication to extremes of self-isolation and cynical manipulation that leaves all that middle ground where we are supposed to be meeting, empty.

And they take time, money, and energy away from building skills to identify and deal with human problems, however they are expressed.

The answer, then, is as frustrating and complex as humans are. Rather than focusing on efficiency, business needs to focus on efficacy or the results that you want. We get bogged down in thinking that finding the right piece, the right worker, through testing will automatically create better worker environments and better teams. But the goal is never to have this vague “betterness” of a team, for example. The goal is always a piece of work, a project, a result. To achieve that you have to think less about personality and work methods and more about the willingness and skills that people bring to the table.

People are allowed to be messy and confusing. They should have that freedom and the freedom to change who they are over a lifetime. And business has no business in trying to stifle that.

Want More Details?

Brown, D. “Derren Brown Astrology.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=haP7Ys9ocTk

Delgado, C. (October 11, 2023). “What Is MBTI: Is the Myers-Briggs Test Still Valid?” Discover Magazine. https://www.discovermagazine.com/mind/the-problem-with-the-myers-briggs-personality-test

Fletcher, J. (August 26, 2023). “What are the Rarest Personality Types?” PsychCentral. https://psychcentral.com/health/rarest-personality-type

Grant. A. (September 18, 2013). “Goodbye to MBTI, the Fad That Won’t Die.” Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/give-and-take/201309/goodbye-to-mbti-the-fad-that-wont-die

Huxley, A. (1932) Brave New World. https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/357838/brave-new-world-by-huxley-aldous/9780099518471

Myers-Briggs.org. “The 16 MBTI® Personality Types.” https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/the-16-mbti-personality-types/

Tolstoy, L. (1865-1869). War and Peace. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhnsky, translators. (2008). https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/208646/war-and-peace-by-leo-tolstoy-a-new-translation-by-richard-pevear-and-larissa-volokhonsky/9780307806581