Photo by Gerard Van der Leun: http://bit.ly/2q5Gxk6

Stories, Stories, Everywhere Stories

I’ve been thinking a lot about endings recently. Not in terms of mortality, but in terms of all the little stories and endings we live through in any given day. These little endings give us comfort. They give us confidence. The feeling of completion is accomplishment, a sense of knowing; you shut the door on something and this gives you a sense of safety.

Maybe I’ve been thinking about these little endings because I spend a lot of my time researching and writing things that take weeks or months, or cough years, before they come together. So, there are days when I desperately need something to finish: to win at Wordle or to bake a cake or even to do a load of laundry simply to get that dopamine fix of having started and finished an action: I completed it; I run through a circle of expectation, action, and ending. Putting away neatly folded warm laundry gives you a feeling of success in the completion of it and that success closes something off and you get a sense of ease, of comfort, as your reward.

Pole Vaulting into Your Heart

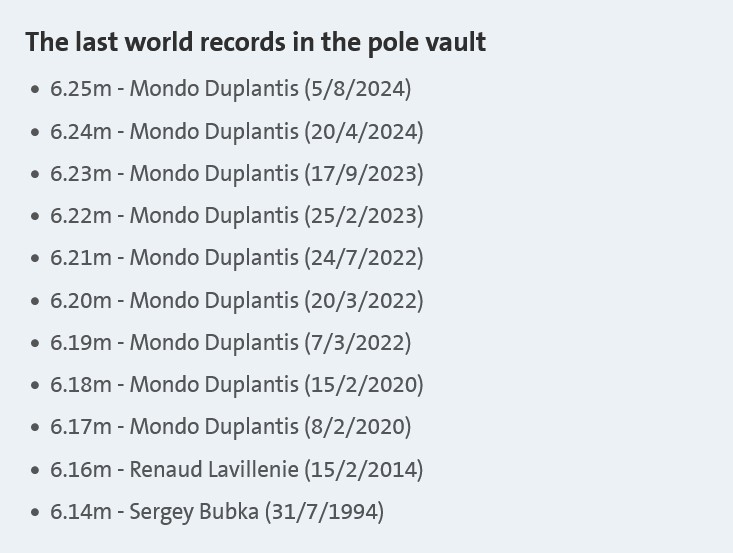

The power of endings and the idea of endings as comfort jumped out at me when I was watching the Olympics this summer and saw the Swedish-American pole vaulter Armand Duplantis break a world record by vaulting 6.25 m. This is incredible on its own, but this is also his nineth world record, having broken the record at least twice a year since 2020 (excluding 2021 because Covid shut everything down).

After his Olympic win, there were articles about the systematization of his increases in height and connecting that pattern to the bonuses he receives from his sponsors and from athletic federations for every win and every world record he smashes. Some articles insinuated that Duplantis was cynically gaming the system.

Before we get into that accusation, let’s take a quick look into the differences between rewards and incentives because it is an interesting muddle. Generally, I think of a reward as happening after an action and is often an unexpected gift. Thus, “When Indonesian badminton gold medalists Greysia Polii and Apriyani Rahayu returned home after the Tokyo Olympics, besides the cash reward from the Indonesian government, local authorities and entrepreneurs also showered the pair with gifts including cows, a house, and even their own meatball restaurant.” Rewards can also be not so unexpected but they’re still vague, such as sponsorship and advertising deals that winning athletes will often get.

Incentives, however, are slightly different in that they are known to exist and athletes can take them into the calculations of their careers. They are laid out like a bonus structure in a company. For example, in the Olympics, different countries offer incentives of hugely different amounts for medals, from USD 700,000 for a Hong Kong gold medal to zero for a Swedish gold medal. Athletic organizations, who regularly give out incentives for their own events used to not have Olympic incentives, but just this year they have started to bring them in. In Paris, for the first time, World Athletics, which is the organization that includes track and field, running, and race walking, offered its gold medal athletes USD 50,000. They are hoping to be able to offer cash incentives for silver and bronze medals in the Los Angeles summer Olympics in 2028.

If you have this added incentive to win and/or get the world record in careers that are usually quite short, then, ironically, the athlete is not really incentivized to go as high or as long as possible in any given meet or event, but to win by as small a margin as possible in order to open up the opportunity to win again at another time and receive another bonus because you are at the top of your career and are taking advantage of the opportunities that this affords.

If you look at Duplantis’ record, he has consistently beaten his own world record over the past four years by a single centimetre each time, and each time he gets a cash bonus from the organizing group or event sponsor. While some see this as cynical manipulation, I don’t think so. It would be wrong to accuse any worldclass athlete of doing their sport only for the money. First of all, because outside of a very few sports, these careers are not huge money makers. Second, as the Norwegian Olympic champion hurdler Karsten Warholm said about the new Word Athletics prize, “It doesn’t change my motivation to win because for the Olympics I’m not in it for the money… The gold medal is worth a lot more to me personally.”

What Duplantis is doing is planning his career, a career he loves and works very hard for. He is maximizing his benefits, of course, but in doing so I would argue that he is also maximizing his sponsors’ and his audience’s enjoyment of his sport.

This brings us back to our topic: endings.

What is happening is Duplantis is giving his sponsors and his audience a satisfying experience, a mini-story, with a beginning — the run — a conflict — the jump — and an ending — a new world record. If you already hold the world record and at a specific moment in time are pretty sure you’re going to win a specific event, then you only need to move one centimetre up to have…..a story. A story that satisfactorily plays out (and pays out). Everyone is happy: we get the ending, he gets the record and the reward.

Duplantis may be making his height adjustments to maximize his career earnings, but he isn’t disappointing anyone. He is taking advantage of our seemingly hardwired need for endings and the comfort and satisfaction they bring.

Joseph Campbell’s Heroic Cycle

In 1949, Joseph Campbell, a professor of English at Sarah Lawrence College, wrote The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which became a huge crossover hit from the scholarly to the popular, having now sold well over a million copies and been translated into over 20 languages. It gained real traction in the 1970s when George Lucas said it was instrumental in guiding him to a final draft of Star Wars. The book looks at what connects myths from around the world, and he found a repeating cycle. Stealing the word from James Joyce, he called this the monomyth:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

If we broaden out the understanding of this journey beyond myth and into our everyday world, we see three broad pillars of need: the departure, the conflict or discovery, and the return. Everywhere you look, we follow this basic pattern to acquire knowledge and alleviate anxiety. We are compelled to question and seek—which creates anxiety—but we also need to complete the cycle and return—which alleviates anxiety.

The human pursuit of this cycle has both positive and negative impacts.

On the positive side: It drives conversation. Conversations are questions and answers, which is just a variation on a story. We want each conversation to come to a satisfying end. Keep this in mind because we’ll come back to this idea at the very end of our own explorations into this topic. Also on the positive side, this cycle drives innovation: pushing us to explore and develop science and technology and to know the human better.

On the negative side: We can be manipulated by our desire to know and our need to alleviate the anxiety of not knowing.

The negatives are really intriguing, but before we get into that I want to spend just a moment looking at the differences between chasing questions of an everyday nature—which is what these episodes are mostly going to be talking about—and chasing the big existential questions. To look at the big questions, I want to look back over a century to a man living underground.

Chasing the Bus of Existential Anxiety

I’ve just finished reading Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. This Russian novel was written in 1864, at a time when science—all science: biology, chemistry, physics, engineering, and psychology—were bursting with new ideas. The speed at which we were learning about the mechanisms of the world, and, through psychology, the mechanisms of the human mind led to the idea that we, as humans, could—in the not so distant future—come to understand everything both outside and inside ourselves.

For Dostoevsky’s character, who is unnamed, and who we will refer to as The Underground Man, this fast-moving discovery of ourselves is a source of anxiety. The anxiety comes from asking the question, “What would happen if we were able to create a user manual for the human and for existence?” He faces the idea that we are chasing down this final existential ending of who we are and our place in the universe. And he thinks that we’ll fight against it. His opinion is that we will fight against knowing everything simply by being human: we are too slippery, too inconsistent, too ungrateful, and too perverse to be nailed down.

The Underground Man is interested in how science will fit into the human, and he notes, laments, and praises the fact that humans cannot be known definitively because we sometimes make decisions knowing that they are bad for us.

I’m going to read some selections from the first part of the book. The translation is stellar and the voice of The Underground Man compelling. The book itself isn’t very long, if you want to read the entire thing. To give you a bit of context, The Underground Man is speaking to imaginary “sirs” who he is having an imaginary discussion and debate with.

“Oh, tell me, who first announced, who was the first to proclaim that man does dirty only because he doesn’t know his real interests…and it’s common knowledge that no man can act knowingly against his own profit, consequently, out of necessity, so to speak, he would start doing good? Oh, the babe! Oh, the pure, innocent child!…What is to be done with the millions of facts testifying to how people knowingly, that is, fully understanding their real profit, would put it in second place and throw themselves onto another path, a risk, a perchance, not compelled by anyone or anything, but precisely as if they simply did not want the designated path, and stubbornly, wilfully, pushed off onto another one, difficult, absurd, searching for it all but in the dark…. And what if it so happens that on occasion man’s profit not only may but precisely must consist in sometimes wishing what is bad for himself, and not what is profitable?”

“…then, you say, science itself will teach man…that in fact he has neither will nor caprice, and never did have any, and that he himself is nothing but a sort of piano key or a sprig in an organ; and that, furthermore, there also exist in the world the laws of nature; so that whatever he does is done not at all according to his own wanting, but of itself, according to the laws of nature. Consequently, these laws of nature need only be discovered, and then man will no longer be answerable for his actions, and his life will become extremely easy…so that all possible questions will vanish in an instant, essentially because they will have been given all possible answers.”

“…if one day they really find the formula for all our wantings and caprices—that is, what they depend on…then perhaps man will immediately stop wanting…. Who wants to want according to a little table?…what is man without desires, without will, and without wantings…. sirs, but for me that’s just where the hitch comes!…You see: reason, gentlemen, is a fine thing, that is unquestionable, but reason is only reason and satisfies only man’s reasoning capacity, while wanting is a manifestation of the whole of life—that is, the whole of human life, including reason and various little itches. And though our life in this manifestation often turns out to be a bit of trash, still it is life and not just the extraction of a square root…What does reason know? Reason knowns only what it has managed to learn… while human nature acts as an entire whole, with everything that is in it, consciously and unconsciously, and though it lies, still it lives.”

“And more than that: even if it should indeed turn out that [man] is a piano key, if it were even proved to him mathematically and by natural science, he would still not come to reason, but would do something contrary on purpose, solely out of ingratitude alone; essentially to have his own way. And if he finds himself without means—he will invent destruction and chaos, he will invent all kinds of suffering, and still have his own way! He will launch a curse upon the world, and since man alone is able to curse (that being his privilege, which chiefly distinguishes him from other animals), he may achieve his end by the curse alone—that is, indeed satisfy himself that he is a man and not a piano key! If you say that all this, the chaos and darkness and cursing, can also be calculated according to a little table, so that the mere possibility of a prior calculation will put a stop to it all and reason will claim its own—then he will deliberately go mad for the occasion, so as to do without reason and still have his own way!”

The Underground Man’s concerns made me think about science, as we know it. We are still in the thralls of a scientific revolution, and with that comes thousands upon thousands of experiments and published articles. In fact, in 2022, 2.82 million scientific papers were indexed on the Scopus and Web of Science databases: that is almost 8,000 papers each day. You would think that we are in the chase of our lives or for our lives. But these papers aren’t focused on the bigger questions. These papers are thousands of small questions and small answers. And the idea that all these small answers might, one day, be pulled together to answer the largest existential question of them all—who are we?—is not really something that is thought about or discussed in scientific circles. But isn’t that the final goal of all science? Are we not continuing to chase what The Underground Man called the “arithmetic” of being human (Ch. 8)?

But not to worry because no matter how far science has taken us, science, like the human, has a kind of perversity to it. Although Dostoevsky’s book was too early to have this metaphor, we can think of this as a dog chasing a bus. The compulsion to chase is there but does the dog give any thought to actually catching the vehicle? What would happen if the dog did catch the bus? The idea gives us dread just as the idea of a world where all questions have been answered gives us dread. As The Underground Man asks, “What is man without desires, without will, and without wantings?” Without questions, what are we? It is an awful idea (in both senses of being terrifying and filling us with awe), so we don’t think about it, but we still chase the bus. We both want and do not want.

Dostoevsky sees our saving grace as the perversity of man, showcased by our love of destruction. The Underground Man says,

“Man loves creating and the making of roads, that is indisputable. But why does he so passionately love destruction and chaos as well? Tell me that! But of this I wish specially to say a couple of words myself. Can it be that he has such a love of destruction and chaos (it’s indisputable that he sometimes loves them very much; that is a fact) because he is instinctively afraid of achieving the goal and completing the edifice he is creating? How do you know, maybe he likes the edifice only from far off, and by no means up close; maybe he only likes creating it, and not living in it.…”

I believe we are perverse and the we don’t really want to reach our greatest goal. We like to see if from far off. But I also think that science and knowledge itself is perverse. It, too, changes and destroys so that we only ever see if from far off. It keeps us from reaching it. We are chasing the bus of science, not really wanting to catch it, but the bus itself seems not to want to be caught. The closer the dog manages to get to it, the bigger the bus grows and the more it changes its shape and duplicates and complicates and shifts itself into something unexpected. The dog could never get it into its mouth, just as we could never get the “everything” of existence into ours.

We’ve seen this happen in our own lifetimes. As fast as science can answer questions, more pop up. Like the mythical Hydra, for every head you cut off, two more emerge. This lets us off the hook a bit and alleviates our anxiety a bit. We have seen that for all the people who claim “soon we’ll know” in any scientific endeavour, we haven’t come remotely close. For example, it’s been seventy years since “the double-helix structure of DNA was first revealed, thanks in part to a grainy black and white image taken by Rosalind Franklin [giving a shout out to the overlooked women of the past], transforming our understanding of how genetic information is stored.” Decades ago, the idea that we could map the human genome suggested that soon we’d be “known” at the molecular level. Leroy Hood expressed the belief that “we will learn more about human development and pathology in the next twenty-five years than we have in the past two thousand” and Science editor Daniel Koshland was touting genetic mapping as the road to knowing everything, suggesting that genes are responsible for poverty and homelessness. These early scientists implied that the human genome was going to be the Rosetta Stone of the human.

Not to worry, though. Returning to Dostoevsky’s human perversity, things got off to a perverse start. The sequencing turned into a race to not only know but to make money from the endeavour. In fact, one company, Celera Genomics, which had partnered with Applied Biosystems to sequence the DNA in three short years, aimed “to sequence and assemble the entire human genome by 2001, and only make the information available to paying customers….[They] also planned to file for preliminary patents on over 6,000 genes and full patents on a few hundred genes before releasing their sequence.” This was in direct opposition to the Human Genome Project’s 1996 Bermuda Agreement, which stated that all information from the project should be made freely available to everyone within 24 hours of being discovered.

A race with prize money, however, means a focus on speed not quality. There were supposed to be different donors of the DNA and each would contribute no more than 10% of the total DNA sequenced in any lab so there’d be diversity in the sample and more readily lean toward the “human” rather than a single person. However, Celera Genomics was using one donor to sequence 70% of the DNA. The doner? Their founder. Why did the founder do this? There are whole books written about the human genome race, but let’s just say as the leader of a company that you think is going to make you very, very rich, it doesn’t seem out of place to have the hubris to want your own DNA to be the foundation stone of all that money. Or, more shortly: humans are perverse and we muddle the very thing we claim to want to see clearly.

If the perversity of the human doesn’t assuage your worries, we can go back to that dog trying to catch the bus that just gets bigger the closer you get to it. The first draft of a human genome was announced to be completed in 2003, but it turned out that this ending was not the great existential ending people worried it would be. They hadn’t really completed it and even in 2023, when the claim was made to have sequenced the first whole person, that wasn’t really the whole story either. In a BBC article, it was admitted that “the efforts to sequence and map the human ‘book of life’ [is] only just the beginning. Far from closing the question of what makes our bodies tick and why they do so differently, research on the human genome has revealed a far more complex picture than anyone could have imagined.”

The rise of AI in the past few years has taken us down a similar, anxiety-riddled road. Will AI, somehow, end humanity? In other words will AI overtake us, mimic us, or make “human” an obsolete and inefficient organism? A piano key that can be played by any computer. Call me crazy, but I agree with Dostoevsky. I think that the human superpower rests in the perverse. For example, AI sometimes has errors that are called hallucinations where it confuses itself but doesn’t think it’s wrong. The key here is that AI can’t differentiate between an error or a correct answer. But the human can not only differentiate but can build itself through hallucinations and build them into something new in the human. Thus, we know the difference between a schizophrenic episode and performance art. And, sometimes, we don’t care. This difference tells me that AI is very far away from being human or even being able to mimic the human.

Science is about experiments and these are all little finish lines, ostensibly building to a big, overarching finish line — the final existential ending — of knowing everything. Of knowing who we are. We fear it, though, and we, knowingly or unknowingly, fight it. Ironically, although we yearn to know the meaning of existence, to create that user manual, to make us all mere piano keys, we also fear what that would look like and mean in terms of being human. So, I don’t think you’d disagree in saying that most of us spend our lives avoiding thinking about the great existential questions, even as we are slowly chasing them with all our smaller questions.

So let’s avoid thinking any more about those questions right now. Let’s go back to the smaller experiences of being. To the multitude of small experiments, small questions, small stories, and human interactions.

Let’s return, then, to our day-to-day encounters with endings, like finishing laundry, or a good book.

That is as far as I will go with this today. My next episode on Patreon will dive a bit deeper into the negative sides of needing endings to our stories by looking at cliffhangers, binge watching, conspiracy theories, and doomscrolling.